Monoplegia: A Localized Paralysis Condition

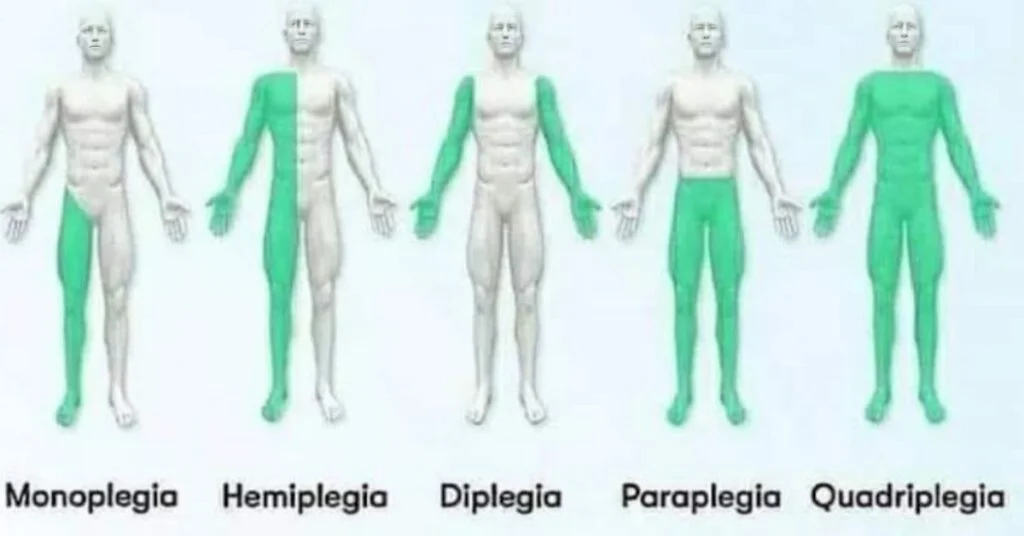

Monoplegia refers to the paralysis of a single limb, commonly an arm, and is typically accompanied by symptoms such as weakness, numbness, and pain in the affected area. Unlike hemiplegia, which impacts one entire side of the body, monoplegia is localized, affecting only one limb or region. When the upper limb is involved, it is termed “brachial monoplegia,” whereas paralysis in the lower limb is referred to as “crural monoplegia.” While monoplegia is less common in the lower extremities, its occurrence can be indicative of underlying neurological or musculoskeletal conditions. The condition is often linked to cerebral palsy and may be an early manifestation of broader neurological disorders, including paraplegia or hemiplegia.

which limb is mostly affected and why?

The upper limb is most commonly affected by MP. This is because the brachial plexus, a network of nerves that supplies the arms and shoulders, is more prone to injuries and disorders compared to the nerves serving the lower limbs. Conditions such as brachial plexus injuries, stroke, and cerebral palsy frequently impair motor function in the upper limb. Additionally, the neural pathways controlling the arms often have a higher likelihood of localized damage in the cerebral cortex or spinal cord due to their complexity and specific anatomical vulnerabilities.

what is meant by monoplegia?

Monoplegia is the paralysis of just one limb, which can affect either an arm or a leg, leading to the loss of movement and sensation in that specific part of the body. and, in some cases, sensation in the affected limb. Unlike other forms of paralysis, such as hemiplegia (affecting one side of the body) or paraplegia (affecting both legs), monoplegia is localized and limited to one specific region of the body. It can result from conditions like cerebral palsy, nerve injuries, stroke, or spinal cord damage, and its severity can range from partial weakness to complete loss of movement.

Practical Guide for Managing Monoplegia

Addressing Weakness and Spasticity

For patients experiencing weakness in the affected limb, strengthening exercises like resistance training or isometric holds can help improve muscle activation. Functional electrical stimulation (FES) is particularly effective in activating weak muscles, enhancing strength, and improving mobility. Stretching exercises and heat therapy are essential for managing spasticity, reducing muscle stiffness, and improving range of motion. Gentle passive movements and daily stretching routines prevent joint contractures and maintain flexibility.

Pain Management and Sensory Re-education

Pain in the affected limb, such as sharp, stabbing sensations or shoulder discomfort, can be managed with positioning aids, such as slings for arm support or elevation pillows for legs. Techniques like transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) provide relief from chronic pain. For numbness or sensory loss, sensory re-education therapy using textured objects or temperature variations helps restore tactile perception. Massage therapy can also improve circulation and stimulate nerve recovery.

Improving Coordination and Movement

To address the difficulty in coordinated movement, constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) encourages the use of the affected limb by restraining the unaffected one. Bimanual training, involving tasks like folding clothes or handling utensils, helps rebuild fine motor skills. Task-oriented training focused on daily activities such as writing or buttoning, aids in functional recovery and builds patient confidence.

Chronic Symptoms and Emotional Support

For patients with progressive symptoms or conditions like brachial or lumbar monoplegia, advanced diagnostics, such as MRI or nerve studies, are crucial for identifying underlying causes like tumors or nerve injuries. Emotional support, including counseling and participation in support groups, is vital to address anxiety and depression that may arise due to disability. Celebrating small milestones and involving family members in the recovery process fosters motivation and resilience.

By combining physical therapy, pain management, sensory stimulation, and emotional support, this holistic approach ensures a tailored treatment plan for each monoplegia patient.

is it severe or more dangerous?

The severity of MP can vary widely depending on the underlying cause and the extent of nerve or muscle damage. In mild cases, patients may experience weakness or partial loss of function in a single limb, often classified as mono paresis, which allows for some movement and daily activity. However, in severe cases, the affected limb may be completely paralyzed, with no voluntary movement or sensation, significantly impacting the patient’s quality of life.

While some forms of monoplegia may improve with therapy and rehabilitation, others caused by conditions like stroke, spinal cord injury, or tumors may result in permanent disability. The presence of additional symptoms, such as pain, spasticity, or sensory loss, often complicates the condition and requires more intensive management.

Types of Monoplegia

MP can be classified into several types based on the affected limb, underlying cause, or presentation of symptoms. Below are the main types:

Brachial Monoplegia

Refers to paralysis of an upper limb, such as an arm. Commonly caused by injuries to the brachial plexus, strokes, or conditions like cerebral palsy.

Crural Monoplegia

Refers to paralysis of a lower limb, such as a leg. Less common than brachial monoplegia and is often associated with spinal cord injuries or localized brain lesions affecting motor pathways.

Complete Monoplegia

The affected limb is entirely paralyzed with no voluntary movement or sensation.

Often results from severe nerve or brain damage, such as a major stroke or spinal cord injury.

Partial Monoplegia (Monoparesis)

Characterized by significant weakness in the affected limb rather than full paralysis.

May progress to complete monoplegia if the underlying condition worsens.

Transient Monoplegia

Temporary paralysis is often caused by conditions like a complicated migraine, seizures, or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). The function typically returns once the underlying issue is resolved.

Progressive Monoplegia

Gradual worsening of paralysis in one limb, often due to tumors, syringomyelia, or progressive neurological diseases like spinal muscular atrophy.

Congenital Monoplegia

Present at birth, frequently linked to cerebral palsy or birth-related nerve injuries, such as neonatal brachial plexus paralysis. Each type of monoplegia requires a distinct approach to diagnosis and management, with treatment tailored to the underlying cause and severity of the condition.

similar symptoms

Differential diagnosis for MP includes distinguishing it from conditions that cause similar symptoms of weakness or paralysis in a single limb:

Hemiplegia: Paralysis of one side of the body, which may be confused with monoplegia if only one limb is affected, particularly in early stroke or brain injury.

Paresis : Partial weakness in the limb, not full paralysis, often due to mild neurological damage and can progress to monoplegia.

Brachial Plexus Injury: Nerve damage affecting the arm, causing weakness or paralysis, often mistaken for upper limb MP.

Peripheral Neuropathy: Conditions like diabetic neuropathy cause sensory and motor deficits in one limb, which may resemble MP.

Stroke: Ischemic or hemorrhagic events in the brain causing localized paralysis, which could be initially diagnosed as monoplegia.

Spinal Cord Lesions: Conditions like syringomyelia or spinal cord tumors that may present with monoplegia but often include other neurological deficits.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Can cause localized weakness and sensory changes due to demyelination, resembling monoplegia.

Cerebral Palsy: In cases of cerebral palsy, monoplegia is often present from birth with permanent neurological impairment of one limb.

Functional Neurological Disorder: Psychogenic paralysis without an identifiable organic cause, potentially mimicking one limb plegia.

A comprehensive clinical examination, neuroimaging, and diagnostic tests are crucial to distinguishing these conditions.